WASHINGTON — U.S. immigration enforcement officers are proposing that fingerprints be taken from all people claiming custody of children who have entered the United States illegally without an adult relative, a measure that opponents said could keep thousands of families apart.

As a new wave of unaccompanied Central American children pours across the U.S.-Mexico border, the proposal underscores the sometimes conflicting goals of federal agencies in dealing with undocumented immigrants, a volatile issue on the presidential campaign trail.

Officials at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which is ultimately responsible for finding housing for migrant children, told Reuters they have no plans to change fingerprinting policy. They said the proposal — made by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials in an internal memo seen by Reuters — would delay family reunions and infringe upon the parent-child relationship.

“One of our goals is to place children with an appropriate sponsor as promptly as we can safely do so. And so any delay for placing the child with their parent is time that we’re keeping a parent and child separated,” said Bobbie Gregg, deputy director for children’s services at HHS’s office of refugee resettlement.

The memo by ICE officials, drafted in response to a February Senate hearing, proposes expanding fingerprinting, now limited to non-parents, to include parents.

ICE says that would allow fingerprints to be checked against an FBI database of criminals to verify the identities of people who say they are parents while ensuring that children do not go to parents who have criminal histories.

The proposal is preliminary and could change. It was unclear whether it would ultimately win the backing of the White House.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) — which oversees ICE — and the Justice Department advise HHS on its practices and have a role in enforcing overall immigration policy.

The White House declined to comment on the proposal.

Asked about the documents that describe the fingerprinting proposal, a Homeland Security spokeswoman said the agency does not discuss internal deliberations. Neither ICE nor HHS would comment on whether they have had discussions on the proposal.

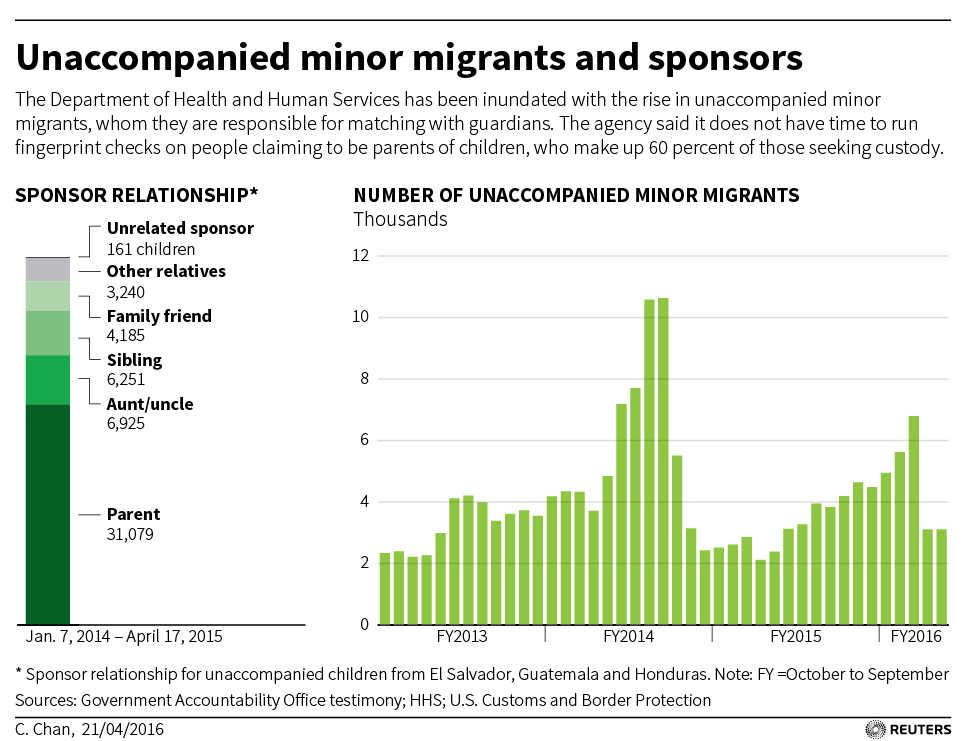

From January 2014 to April 2015, more than 31,000 parents claimed children who entered the United States from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, according to a study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional watchdog unit.

They made up 60 percent of those who claimed children, with most of the rest claimed by other relatives. Only 161 non-relative sponsors claimed children.

U.S. authorities are required to find housing for illegal immigrant minors while they await a trial to determine whether they will be deported, a process that can take years.

Under current law, people who appear at child migrant holding facilities saying they are parents must show the child’s birth certificate to prove the relationship. If that is not available, the parent and child must undergo a DNA test.

Immigration advocates say the ICE proposal would discourage parents from sending for their children and claiming them, fearing that ICE would use fingerprinting to trace undocumented immigrants for possible deportation.

“It could keep parents away from their children if they think it is going to land them in a lock-up somewhere,” said David Leopold, a Cleveland lawyer who formerly headed the American Immigration Lawyers Association.

The ICE officials also said in the memo that the agency supports expanding immigration-status checks to all sponsors, including parents.

ICE acknowledged that conducting immigration checks on parents claiming children could “reduce the likelihood that sponsors would come forward to take custody of children.”

NEW WAVE OF CHILD MIGRANTS

Illegal entry into the United States by unaccompanied minors has surged in recent years. Most are Central American children who make the dangerous journey across Mexico and the U.S. border without their parents, fleeing poverty and violence.

In the six months through March 2016, almost 28,000 unaccompanied children were apprehended crossing into the United States, close to the record-high number hit in the same period in 2014.

An investigation by the Associated Press in January found that HHS had placed some migrant children in homes where they were sexually assaulted, starved or forced into labor for no pay. None of the known abusers had claimed to be parents.

A Senate panel in February asked authorities to improve screening of adults claiming custody of child migrants.

The document from ICE is a draft of answers to questions Senate Judiciary Chairman Charles Grassley submitted for the record following the hearing.

After the AP investigation, HHS said it began doing 30-day follow-up checks on households to which it had assigned a child, while also giving an emergency hotline phone number to all children before they are discharged from HHS custody

But ICE’s response to Grassley said HHS should go a step further, noting that many state and local child protective service agencies routinely fingerprint parents who reclaim children after periods of separation.

JULIA EDWARDS