LOS ANGELES – A California and several other states will honor Cesar Chavez by closing schools and state offices Friday, the 90th anniversary of the birth of a man who went from a grape and cotton picker to an enduring hero for laborers, Latinos and justice seekers of all kinds.

Farmworkers in four states also plan to march Saturday and Sunday in honor of Chavez, who died in 1993, and in protest of President Donald Trump’s immigration policies.

Here’s a look at Chavez, his legend and his legacy:

FROM FARMWORKER TO ORGANIZER

Chavez was born near Yuma, Arizona, on March 31, 1927, and grew up in a Mexican-American family that traveled around California picking lettuce, grapes, cotton and other seasonal crops.

He left school in seventh grade to work full time in the fields and later turned to organizing for farmworkers’ rights.

In 1962, Chavez and Dolores Huerta co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which became the United Farm Workers (UFW) of America.

Farmworkers were crucial to agribusiness in California, which grows nearly half the nation’s fruits, nuts and vegetables, but pay was poor and conditions often miserable.

There were no toilets in the fields for workers, who weeded fields with short-handled hoes that forced them to bend over for hours at a time.

Bosses frequently ignored the health and wages of their workers, many of whom were Spanish-speakers in the country temporarily or illegally and had little political or legal clout to prevent abuses.

GRAPES AND GRIEVANCES

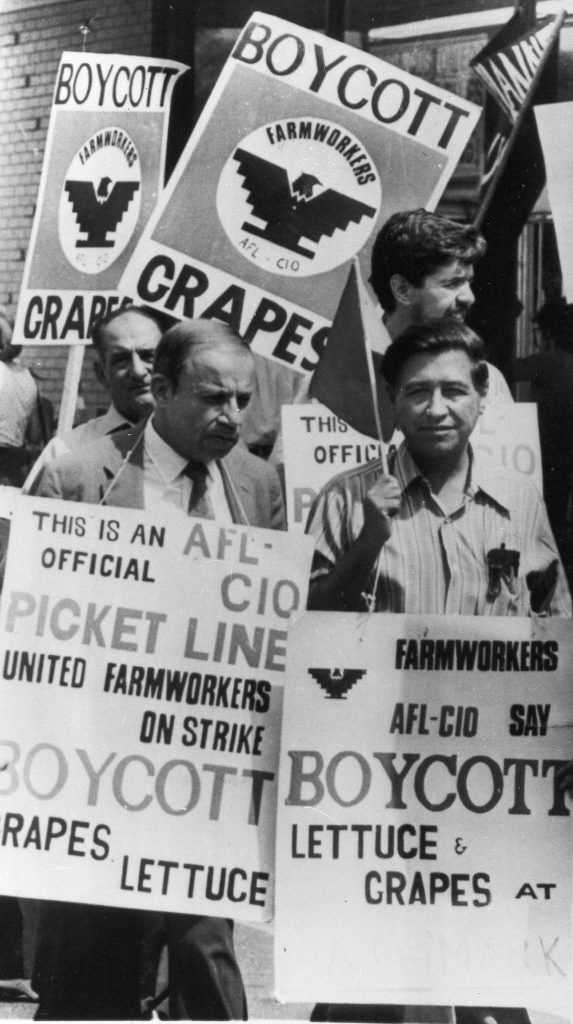

There had been protests and small strikes, but the UFW, with Chavez as its figurehead, helped organize the farmworkers on a large scale and turn their cause into a movement.

The UFW staged nonviolent strikes, boycotts and protests that garnered immense publicity and had a significant effect in California.

A five-year strike that began in 1965 targeted grape growers in the central California town of Delano. Workers demanded pay equal to the federal minimum wage. The fight was marked by a nationwide consumer boycott of non-union grapes, a 350-mile march by grape pickers to the state Capitol and a 25-day fast by Chavez.

In the end, the union reached agreements with growers that covered thousands of workers.

In 1970, nearly 10,000 workers went on strike after lettuce growers and other farmers in the Salinas Valley signed deals with the Teamsters that granted that union — instead of the UFW — the right to organize agricultural workers. It was the largest farmworker strike in U.S. history.

What followed was a boycott that doubled the price of lettuce and a brutal battle with the Teamsters with protests, mass arrests and violence. UFW picketers were beaten and shot, one was killed and a UFW field office was firebombed.

Eventually, the Teamsters signed a deal with the UFW and bowed out of field organizing.

In 1975, the UFW launched a 110-mile march from San Francisco to a winery in Modesto, with more than 15,000 people eventually taking part. A few months later, Gov. Jerry Brown signed a law creating the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) to oversee collective bargaining for farmworkers.

‘SI SE PUEDE’

The union Chavez co-founded now represents only a fraction of the estimated 450,000 people who work in California fields during harvest seasons.

However, he remains an icon of the worker protest movement. His image adorns murals, and his name has been given to streets in Los Angeles; Austin, Texas; and other cities.

His signature protest chant, “Si se puede,” translated as “Yes we can!” became a rallying cry at demonstrations for various causes and even was used during Barack Obama’s presidential campaign.

In 2000, California became the first state to establish a day commemorating the labor leader, held on his birthday. Holidays or other commemorations have been enacted in Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Michigan, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, Wisconsin and Rhode Island.

In 2014, Obama proclaimed March 31 national Cesar Chavez Day, urging Americans to honor Chavez’s legacy. However, it is not a U.S. holiday and federal offices remain open.

‘WE FEED YOU’

About half the people hired to farm crops in the United States aren’t legally authorized to work here, and a large majority of them were born in Mexico, according to federal statistics.

Trump’s pledge to deport millions of people living in the U.S. illegally, build a wall on the Mexican border and withhold funds from “sanctuary cities” that don’t cooperate with federal immigration authorities has struck a chord with this community.

The UFW and other unions have pledged to bring out thousands of people over the weekend in 11 mostly rural communities in California, Texas, Oregon and Washington state.

“Field laborers whose toil supplies fresh fruits and vegetables to America and much of the world will be marching against the Trump immigration agenda carrying ‘We feed you’ banners and signs,” a UFW press statement said.