WASHINGTON – A study that measures the human toll of air pollution from global manufacturing and trade shows how buying goods made far away can lead to premature deaths.

More than 750,000 people die prematurely from dirty air every year that is generated by making goods in one location that will be sold elsewhere, about one-fifth of the 3.45 million premature deaths from air pollution. The study says 12 percent of those deaths, about 411,000 people, are a result of air pollution that has blown across national borders.

“It’s not a single-country issue anymore,” said study co-author Dabo Guan, an economist at the University of East Anglia in England. “It requires global cooperation.”

It has long been known that that the environmental burden of manufacturing often falls heaviest on countries where companies set up shop to take advantage of low labor costs and relatively loose environmental regulations. But this is the first study to bring together economic, manufacturing, trade, atmospheric and health data to calculate the number and location of premature deaths from air pollution.

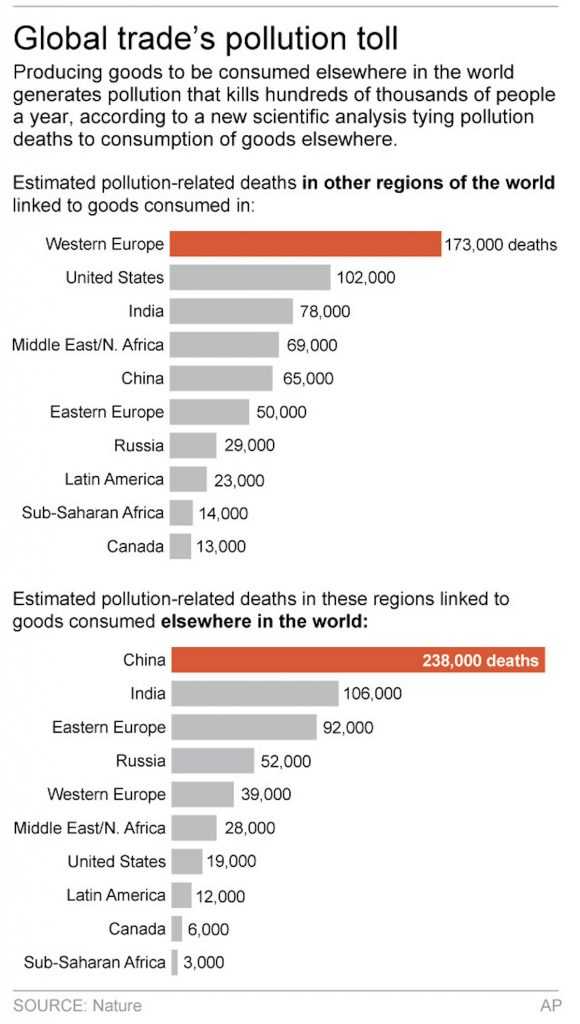

It found that people in Western Europe buying goods made elsewhere were linked to 173,000 overseas air pollution deaths a year, while United States consumption was linked to just over 100,000 deaths, according to the study published in Wednesday’s journal “Nature.”

What that looks like in China: 238,000 deaths a year associated with production of goods that are bought or consumed elsewhere. That number is 106,000 deaths in India and 129,000 deaths in the rest of Asia.

“We have a role in the quality of the air in those areas,” study co-author Steven Davis, an atmospheric scientist at the University of California, Irvine, said in an interview. “We’re taking advantage of our position as consumers, distant consumers.”

Still, the study says three-quarters of the one million air pollution deaths in China — and the nearly half a million deaths in India — are from production of goods that are consumed locally.

China and India also have pollution that travels elsewhere and kills between 65,000 and 75,000 people in other countries, the study said. India’s migrating pollution kills more because China’s pollution, which hits Japan and South Korea, often heads over the Pacific Ocean where its effects dissipate over the miles, Davis said. India’s pollution heads directly to more populous neighboring countries.

The study starts by looking at the 3.45 million deaths a year that this and other studies say are triggered by tiny airborne particles often called soot or smog. About 2.5 million of those deaths are associated with making and consuming of goods, including the energy needed to produce and ship them. The rest are due to natural factors like dust and fires and other causes that can’t be tracked, said study lead author Qiang Zhang, an atmospheric chemist at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Like smoking, air pollution increases the risk of getting diseases like heart disease and stroke, said study co-author Michael Brauer, a public health professor at the University of British Columbia. Using well-established methods, researchers calculate death estimates using health statistics, pollution levels, and other factors.

Dr. Howard Frumkin, a former director of the National Center for Environmental Health at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now at the University of Washington, was not part of the study, but praised it. He said the calculations done by the study are crucial for understanding the larger problem.

“This is a moral question as much as a scientific one,” Frumkin wrote in an email. “But the scientific approach here — linking data on manufacturing and associated pollution emissions, import and export flows, pollutant movement across national boundaries, and the health impact of pollution exposure — is exactly what’s needed.”

Producing more goods locally would change where deaths occur and potentially reduce overall deaths — if local emissions rules are tighter. Bringing back manufacturing to the United States, as President Donald J. Trump and politicians from both parties want, would bring more air pollution deaths to the U.S., but reduce deaths worldwide because pollution laws are stricter, Davis and others said.

Production is likely to remain concentrated in Asia, however, and it will have to be up to those countries to better regulate their own industrial emissions, said Peter Adams, an engineering professor and air pollution expert at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, who wasn’t part of the study. “Relying on consumer altruism,” he said, won’t be enough.

SETH BORENSTEIN