PAPANTLA, Mexico – Guards at one of Mexico’s high security prisons have to worry much more about criminals breaking in than busting out.

Despite a price tag of more than 2 billion pesos ($98 million), the Papantla prison built for about 2,000 men in the eastern state of Veracruz does not have a single inmate, and only a handful of staff look after the site.

So it was not surprising that last year, construction materials were stolen from inside the prison perimeter.

“In reality, it’s a white elephant,” Galdino Diego Pérez, the legal representative for Papantla’s municipal government, said of the enormous white and gray complex outside of town.

The Papantla facility is the most egregious example of wasted taxpayer money under a 2008 prison-building plan that aimed to solve chronic overcrowding in Mexico’s prisons and house an influx of new inmates as security forces cracked down on drug cartels.

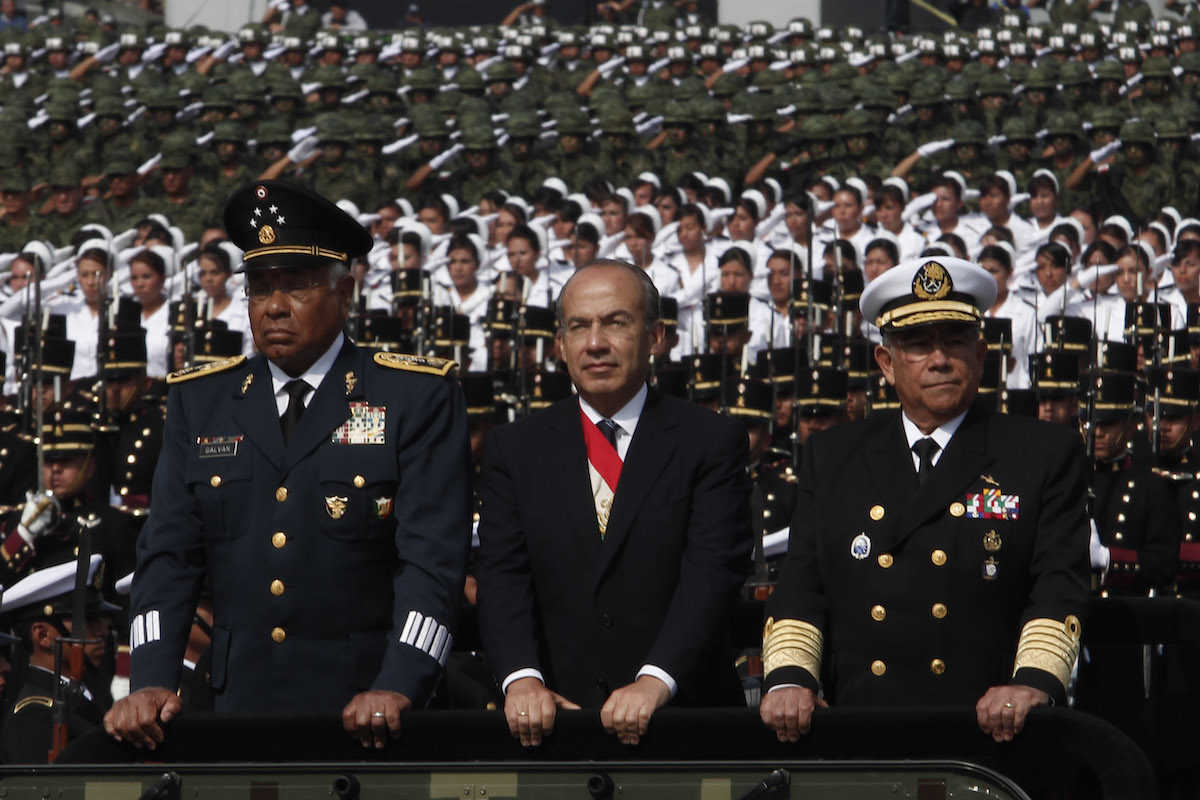

Under the plan, then-President Felipe Calderón’s conservative government gave out some 176 billion pesos of no-bid contracts to open 15 facilities.

But years later, four of them stand only partially built or are still not open.

Public policy experts say the idle prisons reflect inadequate planning by Calderón’s government, though the facilities that were opened did help reduce overcrowding in the penal system.

People involved in executing Calderón’s plan blame current President Enrique Peña Nieto’s administration for the delays.

Most agree, however, that Mexican taxpayers lost out.

More than 2.5 billion pesos of public money has been spent on two of the four idle prisons – Papantla and another in Monclova in the northern state of Coahuila, according to public records.

The others are several years behind schedule and contractors were promised higher future payments under a new plan of partial privatization.

The long delays and wasted money highlight broader problems plaguing government infrastructure programs in Mexico: Congress provides weak oversight of budgets and incoming presidents typically seek to promote their own projects.

“The appetite to build is always what ends up motivating them,” said Manuel Molano, an economist at the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness, a think tank in Mexico City. “It’s badly thought out. It’s a chain of stupidities, complicities and errors from the legislative power to the executive.”

Peña Nieto’s office declined to comment. The prison agency, OADPRS, declined to respond to questions for this story.

WHITE ELEPHANT

The enormous complex at Papantla towers over an impoverished indigenous community, where residents live without drainage and cultivate corn under a hot sun.

“How many billions of pesos invested in this project … with so much need, so much poverty that there is,” said José Simbron, a local farmer. “It’s our money. Everyone’s taxes are there.”

The prison was almost completed when Peña Nieto took office in late 2012, said Patricio Patiño, who was prisons minister under Calderón.

Now the federal prison authority, which has had five different leaders since Peña Nieto took office, has to decide whether to finish off construction of the Papantla prison and open it or scrap the project.

The decaying facility is an added headache for an agency marred by corruption and mismanagement, underscored by the escape from prison of drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera in July 2015.

In the steel town of Monclova, a facility with space for hundreds of inmates closed just a few years after its inauguration. The ill-fated prison, which cost more than 500 million pesos, will not reopen and is instead slated to be turned into a training center for prison agency staff.

PRIVATIZATION

Of Calderón’s 15 facilities, seven were regular construction contracts but the other eight were part of Mexico’s first experiment in privatizing prisons.

Under the model, the contractors do not manage security or health care. Instead they had to find land, raise money, build the prisons and then provide key services like food, laundry and toiletries — but not security or medical care — for 20 years.

Two of those are still not open.

Major security issues have plagued the prison built by Mexican construction firm Prodemex in Buenavista Tomatlán, Michoacán, an area ravaged by drug gang violence.

A former worker said an architect turned up dead during construction, and local news site La Silla Rota reported that a drug cartel at one point took over the site.

Across the country, another prison faced very different problems. In Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila, financial and union troubles weighed on contractor Grupo Tradeco.

A government-mandated location change and decision to turn it into a prison for men instead of for women also held up work, Tradeco’s Chairman Federico Martínez said in an interview.

Patiño, the former minister, said Tradeco was a “disaster” in Coahuila and it had been an error to give the company the contract as it could not meet construction deadlines.

Mexico’s public administration ministry last year barred a unit of Tradeco from taking federal government contracts, without explanation.

The government has not said when either of the two prisons will open. Despite the delays, the companies will be rewarded with larger payments than initially promised.

Both Calderón and Peña Nieto’s administrations raised the payments to Prodemex for the Michoacan prison, meaning the contractor will earn 20 percent more than originally agreed upon, according to records obtained in a transparency request.

The records show Peña Nieto’s government also increased payments for the Ramos Arizpe prison by 18 percent just before it was bought by U.S. asset manager BlackRock Inc.

These moves added billions of pesos to the total cost over 20 years, an additional burden on a federal budget depressed by low oil prices.

The government declined to answer detailed questions about the payment hikes, Prodemex did not respond to multiple requests for comment. BlackRock declined to comment.

MIXED RESULTS

Overall, the prisons that opened have added more than 20,000 spaces, creating room for many federal inmates who would otherwise be housed in state facilities.

Mexico’s state and municipal prisons are notoriously overpopulated, overrun with violence and in some cases governed by the prisoners themselves.

Although better, federal prisons are also understaffed, offer inadequate healthcare and do not do enough to prevent violence among inmates, the government’s National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) has said.

The partially-privatized prisons are no better.

“Despite the investment, it’s no different from a public prison,” said Maissa Hubert at Documenta, a group working for human rights in the justice system.

A CNDH report last fall documented cases of physical abuse, lack of food and some prisoners being locked in their cells almost all day.

There were not enough guards at five of the prisons.

At a women’s penitentiary owned by one of billionaire Carlos Slim’s companies, babies are housed with their mothers but there was no pediatric care, the CNDH said.

This is the government’s responsibility and a spokesman for Slim’s company, Ideal, says it complies with its contract.

On top of the human rights failings, one major injustice persists throughout Mexico’s penal system.

More than one third of all prisoners have not been sentenced, according to government statistics. Some spend years locked up awaiting trial.

“The prisons system is the public policy area most abandoned by the Mexican state,” said Elías Huerta, a criminal defense lawyer who is head of Mexican lawyers’ association ANDD.

“The solution is not more prisons, the solution is a more efficient justice system.”

CHRISTINE MURRAY

JOANNA ZUCKERMAN BERNSTEIN