The Museo del Estanquillo, located in the Historic Center of Mexico City, has opened an exhibition based on Mexican essayist Carlos Monsiváis’ book “Los mil y un velorios” (“The 1001 Wakes”), about the history of nota roja in Mexico.

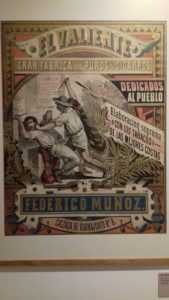

Curated by Mexican cartoonist Rafael Barajas “el Fisgón,” the exhibition includes more than 350 works by artists such as Françoise Aubert, Agustín Peraire, Santiago Hernández, José Guadalupe Posada, the Casasola brothers, Manuel Montes de Oca, Ernesto García Cabral, Nacho López, Adrián Devars, Antonio “el Indio” Veláquez, Enrique Metinides, Fernando Brito and Teresa Margolles.

Since the 19th century, the nota roja has always had an important place among the rest of Mexican news. Its presence pervades much of Mexican culture.

Nota roja can be defined as a niche journalism genre that is massively popular in Mexico. It is similar to general sensationalist (or yellow) journalism, but nota roja focuses on stories and images related to crime, accidents, gore and death. A proposed origin for the term relates to the Mexican Inquisition, which put a red stamp on orders for executions or torture.

Mexican cartoonist Rafael Barajas “El Fisgón,” says that some dissimilar examples include author Vicente Riva Palacio, who wrote the book “El libro rojo” based on bloody historical facts and which was one of this century’s classics among the country’s literature; seminal engravers José Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manilla, who created dozens of flyers containing news and corridos relating to crime, bandits and executions by firing squads; and some of Mexico’s greatest photographers, who developed a career in nota roja, such as Adrián Devars and Enrique Metinides.

Nota roja history intermingles with Mexico’s history. Famous episodes include the brutal murder of the Dongo family in 1789, the Grey Car Band incident, would-be Austrian Emperor of Mexico Maximilian I’s death by firing squad and the killing of Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio in 1994.

Monsiváis said that, in Latin America, nota roja news forces its readers to view details from their own lives under a new, bleak light. He argues that the emergence of narco violence during the last 15 years has forced the nota roja, which was once a niche category, into the daily spotlight. This equates the massification of crime to mass dehumanization.

Two examples of historical nota roja cases are:

—After a summary trial on June 14, 1867, prince Maximilian I was condemned to the death penalty for crimes against the nation, order and public peace by a Mexican military court. Five days later, he was executed by firing squad in the Cerro de las Campanas in the city of Querétaro. His death marked the ending of the bloody fight between Mexican liberals and conservatives. It also ended the second French intervention in Mexico and the short-lived Second Mexican Empire.

News of Maximilian’s execution shook the entire world. Francois Aubert, Maximilian’s court photographer, captured images of the emperor in front of the squad, of his death, and of his corpse. This images were massively reproduced across the world.

—Between 1880 and 1888 in Mexico City, a shoemaker called Francisco Guerrero murdered nearly 20 prostitutes. The killings were gruesome, involving sexual assault, strangulation and even decapitations. Guerrero was the first serial killer in the history of the city. He was known as “El Chalequero,” because of the colorful vests he wore.

Nota roja can be seen as a daily reminder that we are mortals and live fragile, mortal lives; maybe even a sort of modern memento mori.