DALLAS — With the federal government and a Senate committee looking into the dragging of a man off a United Express flight, airlines are beginning to speak up against any effort to bar them from overselling flights.

The CEO of Delta Air Lines called overbooking “a valid business process.”

“I don’t think we need to have additional legislation to try to control how the airlines run their businesses,” Ed Bastian said Wednesday. “The key is managing it before you get to the boarding process.”

Federal rules allow airlines to sell more tickets than they have seats, and airlines do it routinely because they assume some passengers won’t show up.

The practice lets airlines keep fares low while managing the rate of no-shows on any particular route, said Vaughn Jennings, spokesman for Airlines for America, which represents most of the big U.S. carriers. He said that plane seats are perishable commodities — once the door has been closed, seats on a flight can’t be sold and lose all value.

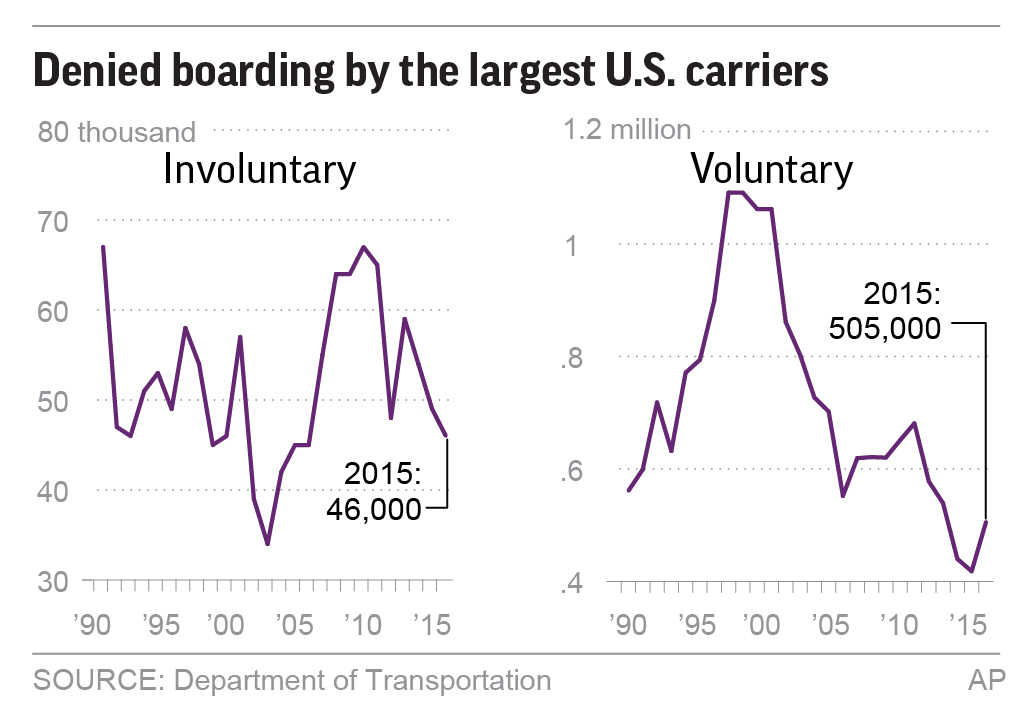

Bumping is rare — only about one in 16,000 passengers got bumped last year, the lowest rate since at least the mid-1990s. But it angers and frustrates customers who see their travel plans wrecked in an instant.

Bumping is not limited to flights that are oversold. It can happen if the plane is overweight or air marshals need a seat. Sometimes it happens because the airline needs room for employees who are commuting to work on another flight — that’s what happened Sunday on United Express.

Flight 3411 was sold out — passengers had boarded, and every seat was filled — when the airline discovered that it needed to find room for four crew members.

That eventually led to the video everybody has seen — a 69-year-old man being dragged off the plane by security officers after refusing to give up his seat.

In a series of three statements and an interview, United CEO Oscar Munoz became increasingly contrite. On Wednesday, he told ABC-TV that he would fix United’s policies and that United will no longer call on police to remove passengers from full flights.

Politicians have jumped on the public outrage.

On Wednesday, 21 Senate Democrats demanded a more-detailed account of the incident from Munoz. A day earlier, the top four members of the Senate Commerce Committee asked Munoz and Chicago airport officials for an explanation.

“The last thing a paying airline passenger should expect is a physical altercation with law enforcement personnel after boarding,” said the committee members, two Republicans and two Democrats. They asked Munoz about his airline’s policy for bumping passengers, and whether it makes a difference that passengers have already boarded the plane.

Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., asked the U.S. Department of Transportation to analyze “the problem of overbooking passengers throughout the industry.” He said was working on legislation to increase passengers’ rights.

The Transportation Department said it is investigating the incident to determine if United violated consumer-protection or civil-rights laws. It gave few details.

New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said Tuesday that he asked the Trump administration to suspend airlines’ ability to overbook flights. Christie, a Republican, said bumping passengers off flights is “unconscionable.” United is the dominant carrier at New Jersey’s largest airport, which is in Newark.

Federal rules require that before airlines can bump passengers from a flight they must seek volunteers — the carriers generally offer travel vouchers. That usually works — of the 475,000 people who lost a seat last year, more than 90 percent did so voluntarily, according to government figures.

United said, however, that when it asked for volunteers Sunday night, there were no takers. United acknowledged that passengers may have been less willing to listen to offers once they were seated on the plane.

“Ideally those conversations happen in the gate area,” said United spokeswoman Megan McCarthy.

Airlines are supposed to have rules that determine who gets bumped if it comes to that. United’s rules, called a contract of carriage, say this may be decided by the passenger’s fare class — how much they paid — their itinerary, status in United’s frequent-flyer program, and check-in time. United has not said precisely how the four people asked to leave Flight 3411 were selected.

United bumps passengers less often than average among U.S. carriers. In 2016, it bumped 3,765 passengers, or one in every 23,000. Passengers were twice as likely to get bumped from Southwest Airlines. Hawaiian, Delta and Virgin America were the least likely to bump a passenger against his will.

DAVID KOENIG